Traum.Land

“AN UNDERLYING SENSE OF DISCOMFORT”

Landscape fragments between untamed naturalness and cultural appropriation

Günther Oberhollenzer

I.

It was a cold, foggy day in November. Michael Goldgruber and I were on our way to Stopfenreuth, the “nucleus” of the National Park Donau-Auen (a nature reserve protecting the Danube wetlands). Right there, in the heart of Lower Austria’s natural and cultural landscape, Goldgruber wanted to talk to me about just how natural so-called wilderness areas really are, as well as about preconceived notions of how to look at things and the way humans encroach on natural spaces. We started our walk from the parking lot at the end of the riverside road. From there we continued along the river, sometimes following pathways, at other times cutting across sand and gravel bars. It was here in December 1984 that thousands of people converged to protest against the planned construction of a hydro-electric power plant – and were successful. That occupation of the Hainburger Au went down as a remarkable episode in Austrian history, and the area has been part of the National Park Donau-Auen since 1996.

More often than not, Goldgruber is out and about in nature on his own. He feels that being there alone makes him more precise, more focused, and hones his perception for seeing and taking photographs. The artist sets out with the images already in his mind, and it is only out there, in the alpine landscape (which is his preferred area of study), that he tries to rediscover and recreate these images. The murky, inhospitable weather at the Hainburger Au is quite fitting, because Goldgruber avoids presenting landscapes in pretty, romantic pictures: idyllic postcard views, sunsets and quietly enchanting, atmospheric depictions of nature are nowhere to be found in his art. For his solo exhibition at the Landesgalerie Niederösterreich, the photographer and filmmaker has taken an in-depth look at Lower Austria’s natural and cultural landscapes. It was an exploratory process lasting many months, involving reconnaissance trips and research that ultimately yielded numerous new works.

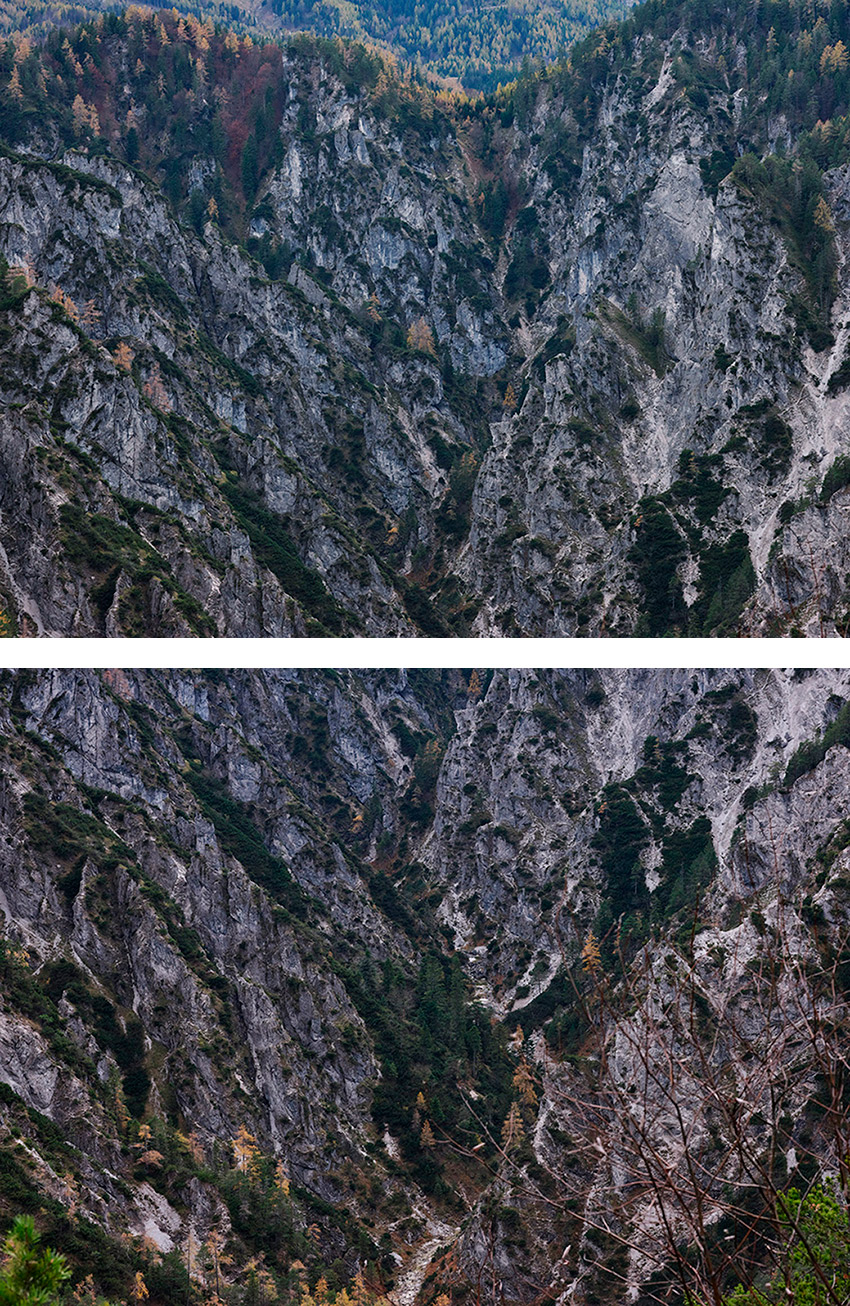

Randsegment, photography, 2019. Fineart pigment print, wooden frame, 120×160 cm

Goldgruber is fascinated by “residual patches” of so-called wilderness, as they still exist in Lower Austria, but especially by areas on the cusp between wilderness and cultural landscape. It is from a very un-tourist-like perspective that he explores places, including the Rax massif, the Alpine area near Ybbsitz including the Ötscher range, the Schneeberg, the Wachau valley, the Waldviertel, the Bucklige Welt or the Wechsel region, to challenge concepts such as unspoiled nature and pristine landscapes that so easily turn into clichés. Goldgruber documents these unassuming peripheral zones in fragmented details and presents them in pictures that may have a casual feel but are actually painstakingly composed. The resulting photographs and films possess high visual appeal, without pandering to the audience or lecturing them. The images speak of expropriation and loss, of constructs and relics, of deceptive naturalness and cultural appropriation.

Randsegment, photography, 2019. Fineart pigment print, wooden frame, 120×160 cm

II.

What images of nature and landscape do we nurture? What images of the natural world can still be presented today? Michael Goldgruber’s work keeps revolving around this question – it also came up during our walk. “Nature is a cultural construct. The notion was invented by humans so as to be able to make distinctions in the environment between what is considered as nature and what is no longer considered to be nature. And the boundaries between the two are arbitrary,” the artist points out. He seeks to shatter this construed image of nature and to open up new artistic stances and perspectives.

One of Goldgruber’s major sources of inspiration is the “New Topographic Movement”, a photography movement that emerged in the USA in the 1970s and is generally seen as the beginning of a new photographic take on the landscape.[i] Until then, photographers such as Ansel Adams or Edward Weston had informed the ideal of modern American landscape photography, guided by a view of landscape and nature largely untouched by humans. The new photographers, in contrast, turned their attention to landscapes or landscape details plainly marked by human intervention. Invested with a critique of civilization, their new type of photography was not concerned with an ideal notion of landscape, but with the documentary view of an environment shaped by human influence and negatively affected by exploitation. Goldgruber counts two of these photographers, Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz, among his role models. Like them, he wants to photograph landscape typologies beyond a traditional concept of beauty, and he finds them in peripheral areas where the boundaries between wilderness and cultivated nature are fluid.

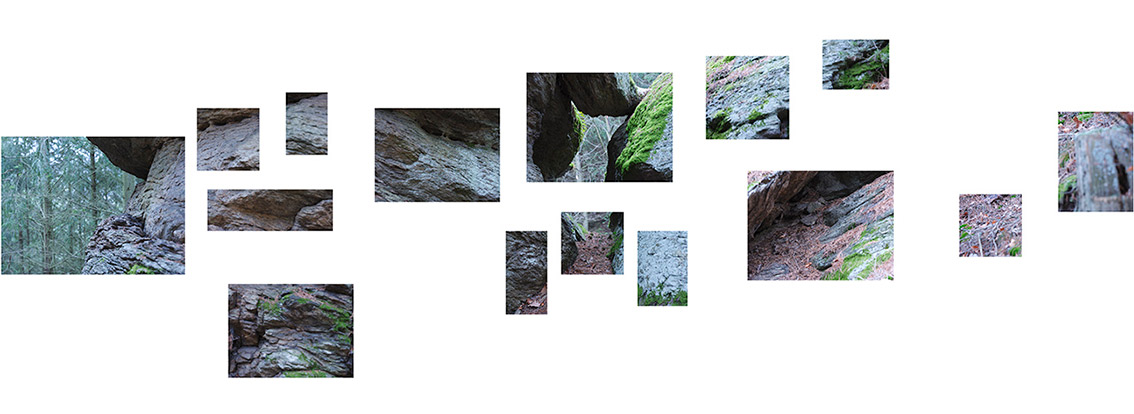

The concentrated photographic details convey an immediate yet unusual impression of nature. By zooming in on landscape structures such as rock faces, snowfields or forest thickets the photographer renders them abstract and difficult to place. Human influence often becomes discernible only at second glance, for instance in the form of concrete elements or slope reinforcements in the midst of roadside vegetation. In the large panoramas, which are assembled from several hundred individual images, the artist deliberately picks up on the notion of an idyllic postcard picture. He fragments the view into hundreds of individual images with omissions and overlaps, thereby exposing the construed nature of the regime of panoramic apperception.

[i] The name derives from the exhibition “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape”, which was shown in 1975 at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York.

Randzone, photographies, dyptich, 2020.

Kollisionsschichten, photography, 2019. Fineart pigment print, wooden frame, 100×133 cm

Einschnitt, 2020, wall-installation, appr. 400 colour copies, dimension 3×8 m

III.

In Central Europe, human settlement has left its mark on all but a few virgin landscapes. While the media like to try and present these residual patches as typically characteristic of a certain region, especially in the Alps, they are only small islets that are surrounded by cultural landscapes. Nor are they really untrammeled by human influence, as that influence is all too visible and perceptible even inside the nature reserves (Goldgruber and I suddenly got a pungent whiff of food coming from one of the passing tourist boats as we walked along the Danube bank, for instance). On the other hand, nature does not heed the limits and regulations defined by humans. Goldgruber cites the wolf, which has now returned to Central Europe, as a case in point. The wolf does not care whether its habitat is a designated nature reserve or a cultural area. It goes where it finds good living conditions. In his photographs, the artist portrays the wolf almost as if in a hidden-picture puzzle, barely visible behind a tree or just as a blurred spot. In a film, Goldgruber presents the wolf expert Kurt Kotrschal, who speaks about the cultural history of the wolf and the current challenges in human-wolf coexistence.[i]

Photographed with marked reticence, Goldgruber’s wolf pictures differ significantly from the images we are familiar with from elaborately produced television documentaries or over-aestheticized photos in the social media. There are no close-ups, no dramatic animal scenes with perfect lighting. The artist takes particular issue with nature documentaries such as the Universum series or Terra Mater. Quite often, their imagery–elaborately staged with pathos and time lapse, dramatic music and silky-voiced commentary–bears little resemblance to an authentic perception of nature. In its perfect composition, it is certainly kindred in spirit to the affirmatively romantic paintings of the 19th century, intended to convey an idyllic natural world to an urban audience.

[i] An edited transcript of the video can be found in the exhibition catalogue

Appearance, photography, 2019. Fineart pigmentprint, wooden frame, 46×60 cm.

Appearance, photography, 2019. Fineart pigmentprint, wooden frame, 65×85 cm.

Appearance, photography, 2019. Fineart pigmentprint, wooden frame, 65×85 cm.

IV.

“The photograph of a landscape is always simultaneously a political and social account, embedded in a past or current context,” notes Goldgruber. “There is no such thing as an image of nature bereft of meaning.” The artist thus ties in with the tradition of James Benning, whose work he also describes as an important source of inspiration. In long, static shots, the American filmmaker Benning takes a meditative look at archaic nature and human technology impinging on it. Goldgruber works along similar lines: his quiet films contain no cuts, music or hectic tracking shots, and they focus on a single image motif. “As I look at a physical landscape, I always see it as a social or political landscape as well,” emphasizes Benning. “It lets you read the political status of a society: who owns the land, what do they do with it? Who profits from it and who works on it?”[i]

Goldgruber’s (and Benning’s) works are not about current affairs, they are not about exposing the obvious destruction of nature. As a politically minded individual he is interested in current ecological debates, but as an artist he is not. His work is far from being an ostentatious expression of concern, naming and shaming environmental sins or human failures in nature conservation.

In the past, Goldgruber frequently photographed structures and architecture built to observe and control landscape and culture, thus showing directly visible human intervention in nature. In the Lookouts photo series, for instance, he documented tourism-related interventions in nature and the impact of mass tourism and the leisure industry on what were supposed to be indestructible mountain massifs. Humans occupy natural spaces and make them user-friendly, building observation platforms as apparatuses of perception that resemble flashy landmarks of a regime, or temples of a new religion. A fixed, human-directed viewing point instructs the masses what to see and how to take in the landscape. The mountain tourist thus becomes a consumer of nature. Goldgruber takes a step back and grants us an unusual view of nature, far removed from the advertising aesthetics of tourism. The man-made viewing point and the architectural user interface form an integral part of his image of the landscape.

These topics still interest Goldgruber, but his current work demonstrates that even purely topographical conditions can tell us a great deal about the relationship between humans and nature: a glacier in times of climate change, erosion and landslides in a ski resort, a dark, monotonous forest. The slightly underexposed photographs and films of spruce trees are particularly unsettling. The forest appears gloomy, monotonous and dreary; its regimented lines, almost as if designed on the drawing board, reveal human interference. As a domesticated monoculture, the forest becomes a profit center for humans, following their (profit-oriented) laws and no longer, or only to a limited degree, those of nature. For the artist, the sprucescape is a “visual code” for an appropriation of natural space, for a rigorously structured cultural and economic zone.

[i] “Eine Landschaft verstehen, indem man ihr beim Werden zuschaut”, James Benning in conversation with Dominik Kamalzadeh, found at: https://www.derstandard.at/story/259125/eine-landschaft-verstehen-indem-man-ihr-beim-werden-zuschaut (accessed on 1 February 2020); quote translated from the German.

Restmodul, photography, 2019.

“We are fully justified in saying that the ground that surrounds us contains its history recorded in its countenance.”

Friedrich Simony, 1876

Restmodul, photograhies, dyptich, 2019.

V.

“We are fully justified in saying that the soil that surrounds us contains its history recorded in its countenance,” wrote the geographer and alpine researcher Friedrich Simony[i]. Goldgruber values Simony’s photographs, especially those taken by the latter during his exploration of the Dachstein region from 1875 onwards. While they were created for purely scientific purposes, the high aesthetic quality of these images is undeniable.

Goldgruber likes the approach of the natural scientist; he sees himself as a visual artist, but one who looks at the world with an inquiring eye and approaches nature in the spirit of a documentarist as well. The artistic challenge lies in using deliberate image selection and composition to go beyond the purely documentary, and also in the ability to reveal what one intends to show in the first place: “A photographer can make an impression not only by developing a certain aesthetic or a specific view on certain phenomena, but also by his ability to access subjects that are not accessible to others. Subjects that can only be captured on photograph […] as a result of great effort and after extensive research,” as aptly described by art historian Wolfgang Ullrich.[ii]

[i] Friedrich Simony, “Die Landschafts-Photographie in ihrer wissenschaftlichen Verwerthung”, in Photographische Correspondenz, issue 146 (1876), 105-111, here specifically p.106.

[ii] Wolfgang Ullrich,” Der Vorstellungskraft auf die Sprünge helfen!”, in: Lois Hechenblaikner: Winter Wonderland, Verlag Steidl, Göttingen 2012, 92-95, here specifically p.92.

Roadside, photography, 2019.

Fortification, photographies, tryptich, 2019.

Goldgruber knows the danger, and perhaps also the temptation, of photographic uniformity; he is reluctant to add to the hundreds of millions of landscape photographs that are available on the Internet from all regions of the world. The artist also wants to shed what he feels to be the yoke of romantic pictorial systems. “You have to be able to refuse some images,” he says, “in order to arrive at a relevant image.” Goldgruber is very often out and about in nature, but he only takes a few photographs and sometimes returns without taking a single shot. In an age when people constantly take photographs, this reticence has to do with escapism and distinction. Each picture is preceded by a preparatory process, and the artist spends a lot of time on site, exploring the motif for a long time until everything is just right: location, composition, details, lighting and lines. As a viewer one can sense this quality in his pictures.

According to Goldgruber, an image has to “work”. His photographs exhibit a certain lyrical aloofness and intuitive nonchalance, but also, at the same time, a sharply honed critical perception. They are situated between the poles of documentation and poetry, without being either didactic or an obvious illustration of ecological aspects. They may resonate with a very subtle romantic undertone, which is still characteristic of how we Europeans perceive nature. Goldgruber is far from being a denier of romanticism; indeed, critical exploration of the romantic aspects of nature has helped him find his personal point of view.

Another artist with a very direct, authentic and penetrating view of nature and its perception by humans is Bodo Hell. For 30 years, this avant-garde Austrian writer has been spending his summers at an alpine abode on the Dachstein. Asked for a contribution to Traum.Land by Goldgruber, who feels a sense of kinship with the writer, Hell has created a text full of perceptive observations and intriguing word cascades.

Iterative Itinerare, Installation, 1,5 x 8 x 2 m, Text by Bodo Hell, graphic design of the script roll by Stefan Biedermann. Solo show “Traum.Land”, State GAllery of Lower Austria, Krems, 2020.

Randbestand, photographies, dyptich, 2019.

Einschnitt, photographies, dyptich, 2019. Fineart pigmentprints, wooden frame, 85×105 cm.

VI.

Back from our walk I reflected on our conversation. Michael Goldgruber is an intuitive and thoughtful artist with a special take on nature. His is not the gaze of an environmental activist or social critic seeking to denounce environmental sins, mediatization or the economic exploitation of nature; nor is it the uncritical, naive gaze of an inexperienced wanderer. His is the sharp, critical and affectionate gaze of an authentic nature lover and passionate observer. His photographs and films demand time, attention and the willingness to engage with the images. When you walk through the exhibition or browse through the book you will probably be surprised not to find those images of nature that are familiar to you from Lower Austria. Incidentally, the exact location is not really important, since the pictures are representative of Central European landscapes to be found in the same or similar form in other regions. Perhaps you will experience a degree of irritation or even discomfort. At any rate, however, Goldgruber makes us more aware of how strongly everyday perception is conditioned by the human gaze, how lastingly natural areas are shaped by a cultural influence and how diverse cultural landscapes can be today.

Randsegmente, photographies, tryptich, 2019. Fineart pigmentprints, wooden frame, 46×60 cm.

Blockmodule, photographies, 2020. Wall installation, various dimensions, wooden frames.